In Australia, we call them grey nomads. They are the tens of thousands of Australian retirees who take to the road in caravans and campervans for several months every year in search of warmer climates.

Elsewhere, these migratory senior citizens are known as snowbirds. In China, they number in the hundreds of thousands and many of them fly south every year to the tropical city of Sanya on Hainan Island, swapping frigid northern winters for sunglasses and sand between their toes.

The growing number of elderly migratory holiday-makers is just one sign of a profound social shift taking place around the world, one that has ramifications for everything from economic growth and healthcare costs, to welfare systems.

Globally, people are living longer and having fewer children, and governments are scrambling to deal with what that means for families and retirement pensions, and the cost of care for the growing number of elderly citizens.

The 21st century is truly the ageing century, says John Piggott, a scientia professor of economics at UNSW Business School. Piggott is director of the ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR), an alliance of Australian and international universities, and government and industry leaders, hosted by UNSW Business School.

CEPAR’s contribution to our understanding of international demographics was recognised last year when Piggott was appointed co-chair of the Think20 Task Force on Aging Population for G20 countries.

'China represents one-fifth of the world’s population and has probably one-quarter of the world’s people aged 60 and above'

JOHN PIGGOTT

Global time bomb

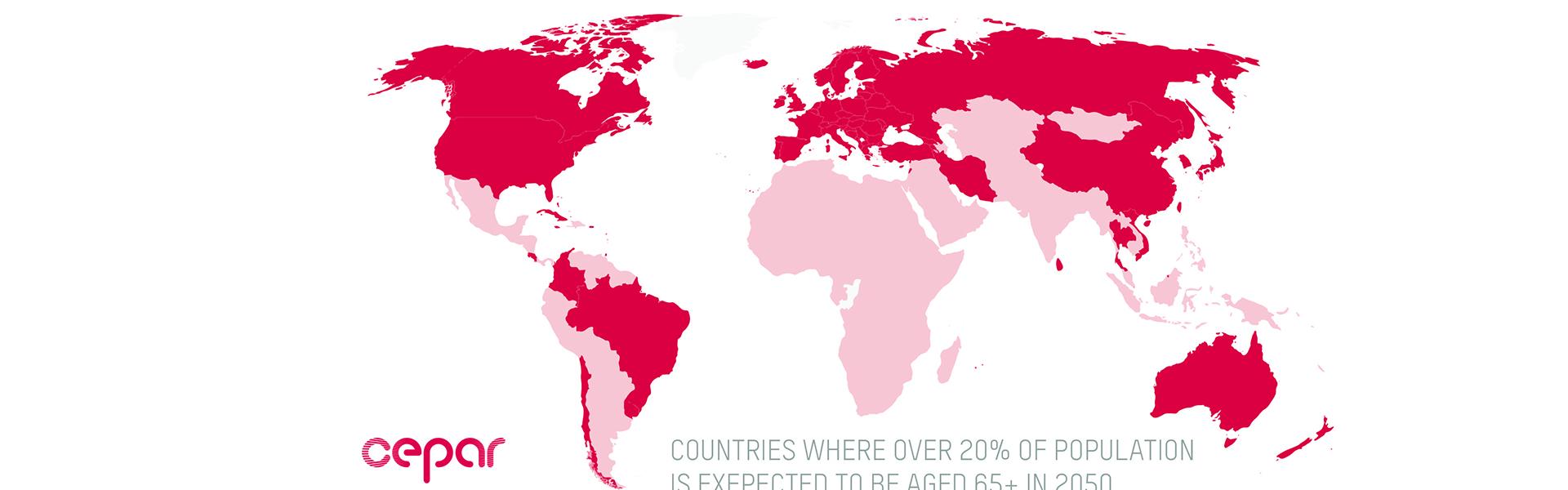

The rate of population ageing this century will be greater than any other. CEPAR calculations based on UN data show that by 2050, there are expected to be 83 countries with more than 20% of their population aged 65 and over, representing an unprecedented burden of care for younger people and governments.

Those aged 80 and over – the most likely group to require care – is projected to reach 430 million. That’s up from about 14 million in 1950 and 125 million now.

But it is what’s happening in China that could have the biggest impact on the rest of the world, says Piggott, who also heads up a special research team in CEPAR, established in 2015 with UNSW funding, that focuses on the pension, social security and health implications of population ageing in China.

Via workshops, conference presentations and visits to leading research institutions in China, the Australia-China Population Ageing Research Hub has become an important voice in policy debate in China.

Developed nations have also aged but in China it is happening much faster than it occurred in the West, says Piggott. That means the world’s second largest economy is getting old before it gets rich and that will have major ramifications for patterns of production and consumption, investment and interest rates in China and the rest of the world.

“It is a huge global issue. China represents one-fifth of the world’s population and has probably one-quarter of the world’s people aged 60 and above,” he says.

“And, if you look at the projections for people aged 80+, China’s share is growing quite significantly. Life expectancy is increasing and the population is so big to start with that it means China will be more substantially represented in the 80+ demographic in the next generation.”

Those demographics will change China’s aggregate growth and its patterns of consumption and expenditure, he says, but the significance of the inevitable flow-on to the world economy has not been fully recognised.

Major social consequences

“I think it is likely that because you will have a higher proportion of the population supported by retirement incomes rather than by labour, the consumption mix in China will change and be more focused on service delivery,” explains Piggott, “and that may have impacts for Australian exports, for example.

“At the moment, a simplistic view of what goes on between Australia and China is that when the Chinese economy looks fragile, [the government starts] another infrastructure project and that requires resources from Australia and elsewhere.”

But that could change, he says, if there is more demand in China for retirement and aged care services, for example, rather than natural resource-intensive projects.

Internally, China is facing major social consequences stemming from the confluence of rapid growth – often fuelled by people moving from rural areas to cities – with a rapidly ageing population.

With fewer children to look after ageing parents and young workers leaving their home towns to seek work elsewhere, policy challenges include providing and funding care for the elderly, raising China’s retirement age for urban workers (60 for men, 50 or 55 for women), and creating a stronger market for retirement income and financial products, and housing.

The China research hub has worked on alternative retirement settings, on decreasing contributions to private pensions, on the creation of equity release systems (for example, reverse mortgages), and on what the demand for long-term care might be as overall life expectancy increases.

‘The work we are doing can help inform the nature of those debates’

JOHN PIGGOTT

Paying for the elderly

Last August, CEPAR hosted the 4th International Conference of Long-term Care Directors and Administrators, which attracted more than 80 international and domestic academics, policy-makers and industry leaders to discuss the challenges and solutions in the aged care sector.

It’s an area that has attracted the attention of the federal government’s trade and investment promotion agency, Austrade, because of the opportunities for Australian businesses to help China close the care gap between its ageing population and the availability of aged care services.

Although far from a perfect system, in Australia, retirees benefit from a well-established aged care market that provides public and private services ranging from those delivered to people still living at home, through to retirement villages and nursing homes. Public and private pensions help pay for those services.

In China, the question of who will look after the elderly is not as clear. The breakdown of the traditional family means many ageing parents won’t be looked after by their children. And for every snowbird enjoying a Florida lifestyle in Sanya, there are plenty of other elderly people who face hardship and poverty.

The Chinese government has stepped in to provide some home care services, says Piggott, and it is considering raising the retirement age and cutting pension contributions, among other policies.

“The work we are doing can help inform the nature of those debates.”

Find recent related papers on the BusinessThink research page.

This article was originally published on Business Think, UNSW Business School's new digital platform for connecting industry to business research. Subscribe to BusinessThink.