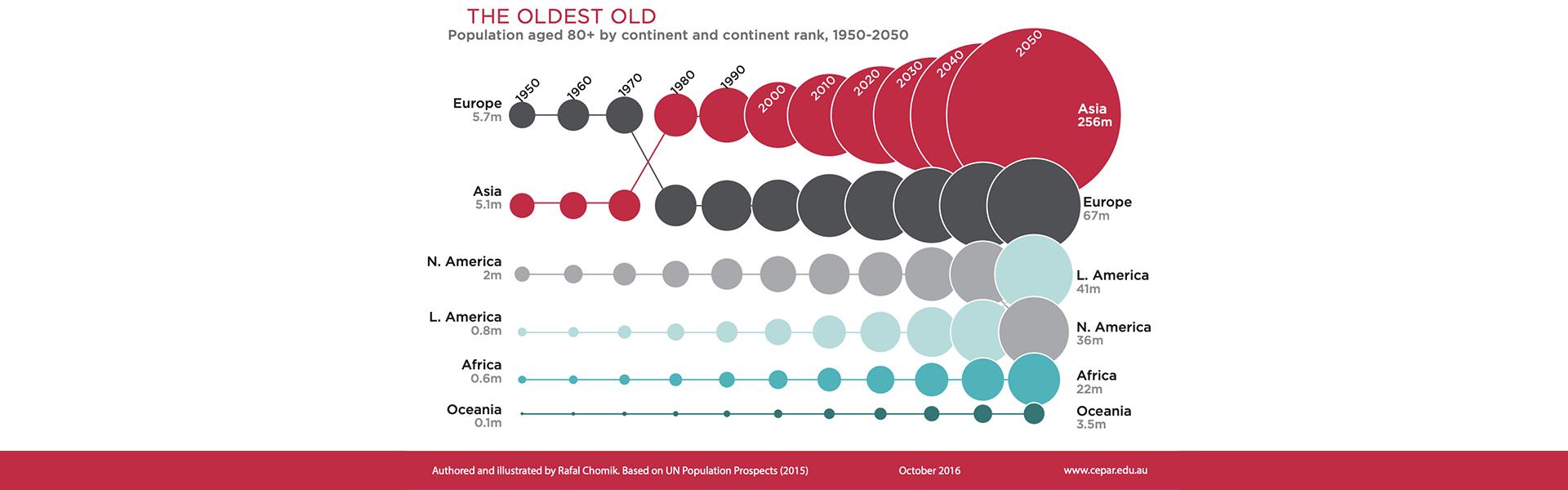

Image: Graphic of the 'Oldest Old': Population aged 80+ by continent and continent rank 1950-2050. Source: CEPAR Fact Sheet, The Conestallations of Demography

For the 2020 World Population Day on 11 July, CEPAR is featuring a previously published fact sheet* by CEPAR Senior Research Fellow Rafal Chomik - The Constellations of Demography – offering a visual representation of what are the most staggering global demographic shifts in modern history.

View or download the CEPAR fact sheet The Constellations of Demography here.

The following article is republished in parts from CEPAR's Media Release and has been updated. Read the original article.

The world’s population has grown rapidly from about 2.5 billion in 1950 to 7.8 billion in 2020 and is expected to rise to 9.7 billion by 2050. But this is accompanied by a demographic transition that is taking place at different rates in different places.

“The CEPAR fact sheet helps you see patterns that you might not otherwise notice by looking at tables of data. When you chart it up, the data doesn’t change but how you view it does. Taking a global view also puts local demographic changes in perspective, especially since we look here at absolute numbers of people rather than proportions within a population,” says Rafal Chomik, CEPAR Senior Research Fellow at UNSW Sydney.

These demographic shifts will have implications for the patterns of production and consumption, investment and interest rates, and social and diplomatic institutions.

“Take Nigeria, for example,” says Rafal Chomik. “It is already the most populous country in Africa, but by 2050, the size of its potential pool of labour is expected to eclipse the US. By then, the size of Germany, Italy, and France’s working-age populations will fall out of the top 25 countries. So it has implications for where economic activity might shift with the right types of institutions.”

Another striking pattern relates to the absolute size of the retirement age populations (65+) and those most likely needing care (80+). In 1950 the 80+ population was only 14 million (0.56% of the total population) but by 2050 it is projected to be 430 million (4.4%). The fact sheet shows which continents and countries will be home to these older populations.

Australia is not featured among the top 25 countries with respect to total population (it ranks about 50th), yet the country is within the top 25 when it comes to those aged 80+.

“So while Australia may be preparing for an Asian century, it should also be ready for what will be an ageing century,” says Rafal Chomik.

By 2050, China is expected to have over 370 million people aged 65+, and countries such as Bangladesh and Vietnam will have more older people than the demographically advanced countries of France or Italy.

“All this raises lots of questions for us as researchers but it also has implications for government and business in Australia. How will the social security systems in these countries cope and what level of technical assistance might they need to make pension and health systems stable, sustainable and adequate? Who will look after the 120 million Chinese aged over 80 if they need help with daily activities? And how will the patterns of trade change? Will Africa become the new workshop of the world?” asks Rafal Chomik.

* The CEPAR fact sheet The Constellations of Demography was first published in October 2016.